Interpreting Machine Learning Models - Part 1

13 Jul 2019Link to start of the blog series: Interpretable ML

This post explores the different types of interpretability, relationships, consequences and evaluation of machine learning interpretability.

Types of interpretability

-

Intrinsic interpretability: This type of interpretability involves machine learning models that can inherently be interpreted. For example, a short decision tree can express visually the thresholds of splits at every level. A simple linear regression can also show the importance given to each feature. In this scenario, we do not need to resort to any other methods to interpret the models other than to inspect the learned parameters themselves.

-

Post hoc interpretability: This type of interpretability involves machine learning models that are difficult or impossible to interpret by human standards. For example, just looking at the neural weights of neural networks offer no explanation whatsoever regarding the interpretability. In this scenario, we try to explain the behavior of a model after it is trained by observing how it behaves in myriad situations. This type of interpretability can be applied to interpretable machine learning models too, like a complex decision tree or a linear regressor.

Relationship between algorithm transparency and interpretability

Machine learning algorithms with a high level of algorithm transparency usually tend to have a high interpretability. Algorithm transparency is a measure of how well the learning algorithm is studied and how well we can correlate the learning algorithm with the learned features. For example, in a k-means clustering algorithm, we use a distance metric to classify the points. We know exactly the vector space in which the distance is calculated, the distances between the cluster center and how we decide which cluster a point belongs to. Hence, we can say that k-means has a high level of algorithm transparency. Contrast this with a convolutional neural network and the difference becomes obvious. Although we do understand on a high level that the lower layers differentiates on lower pixel level like contrasts/edges while the higher layers learn more semantic features of the image, we do not yet understand how the gradient updates (irrespective of the algorithm used) in the higher layers, which trickles down to lower layers, correlate to identifying specific features of the image. This is an extremely exciting area of research that I am personally interested in.

Evaluating Machine Learning Interpretability

Before we go further into “how” to achieve interpretability, we need to first understand “what” we are trying to achieve. How do we evaluate different interpretability models? How do we know which method is superior than the other?

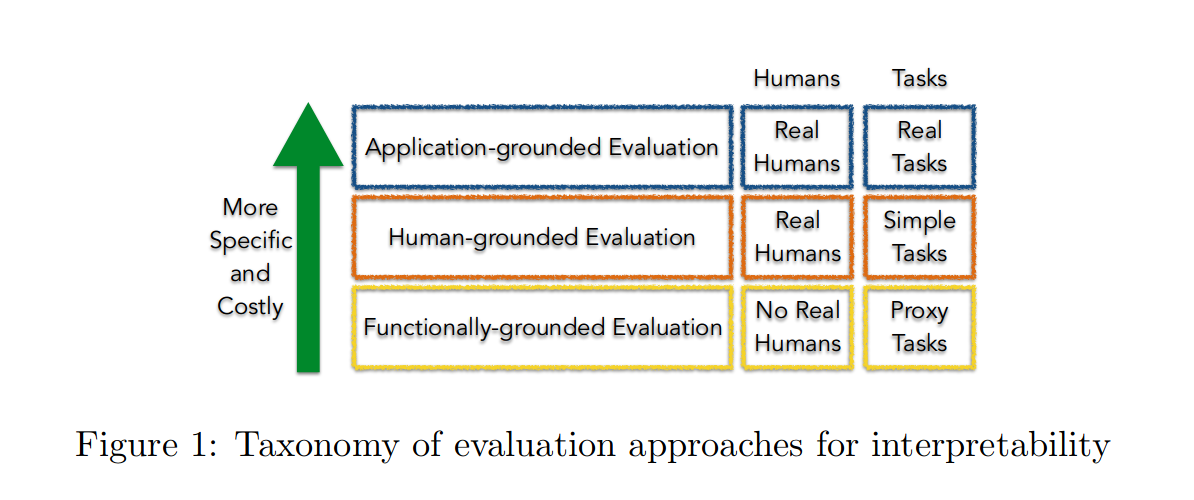

Doshi-Velez and Kim (2017) proposed a three level evaluation metric:

- Application grounded evaluation

- Human grounded evaluation

- Functionally grounded evaluation

-

Application-grounded evaluation (Real humans, real tasks):

This involves conducting human experiments within a real application. Domain experts are involved to verify the correctness and usefulness of the interpretation offered by the model. For example, a model which predicts whether a tumour is malignant or benign can produce a prediction along with an interpretation report which a doctor can verify.

This can also involve not making a prediction and only offering supporting evidence to the domain expert in order to make his task easier and faster to accomplish. For example, in the previous example, a model can mark regions of X-ray images which it might flag as malignant/benign which the doctor can incorporate in his decision making.

-

Human-grounded metrics (Real humans, simplified tasks):

What happens when we do not have access to domain experts or if the model does not necessarily replicate a domain expert’s task? In this type of evaluation, we make use of lay humans who do not possess any prior knowledge of the task or the underlying model. This can be accomplished through the following 3 ways:

-

Binary forced choice: Humans are presented with pairs of explanations, and must choose theone that they find of higher quality (basic face-validity test made quantitative).

-

Forward simulation/prediction: Humans are presented with an explanation and an input, andmust correctly simulate the model’s output (regardless of the true output).

-

Counterfactual simulation: Humans are presented with an explanation, an input, and an output, and are asked what must be changed to change the method’s prediction to a desiredoutput (and related variants).

-

-

Functionally-grounded evaluation (No humans, proxy tasks):

In situations where we cannot leverage humans for testing (for cost, time or ethical reasons), we can use a proxy for evaluation. This seems a bit counter-intuitive since interpretability requires human comprehension. This type of evaluation, hence, is applicable to models whose counterparts are already subjected to some form of human evaluation. This type of evaluation requires further research.

Unintended consequence

One very interesting consequence that will arise if we manage to build/train a very good interpretation model for existing models is that we can ultimately use the explanations provided by the interpretation model to make the prediction itself. If the interpretation model is actually good, we can as well eliminate the complex underlying machine learning model itself. There would be no need to have the deep neural networks with millions of parameters. Of course, this can spiral into a recursive problem where the interpretation model itself becomes complex enough to require another interpretation model. That would be a very interesting situation to be in :P