Google Search by Voice - Case Study Summary

05 Feb 2019This blog post is a summary of the case study made by Google when it first launched it’s voice services. For any company/person trying to undertake this endeavor of building a voice product, this early stage case study is a huge knowledge bank. For one, it is always better to learn from someone else’s mistake rather than our own and two, majority of the underlying architecture of Google’s voice platform has remained the same over the years. Going through this case study gives us an important insight into how Google does voice.

The original case study file can be found here

If you are new to Speech and Speech Recognition, I would recommend you to start here: Introduction to Automatic Speech Recognition

GOOG-411

GOOG-411 was a domain specific Automatic Speech Recognizer(ASR)/Language Model(LM) for telephone directory listings.

GOOG411: Calls recorded... Google! What city and state?

Caller : Palo Alto, California

GOOG411: What listing?

Caller : Patxis Chicago Pizza

GOOG411: Patxis Chicago Pizza, on Emerson Street. I’ll connect you...

Instead of 2 separate queries, in 2008 a new version of GOOG-411 was released which could take both entities as input in a single sentence.

GOOG411: Google! Say the business, and the city and state.

Caller : Patxis Chicago Pizza in Palo Alto.

GOOG411: Patxis Chicago Pizza, on Emerson Street. I’ll connect you...

In November 2008, Voice Search was first deployed for Google app users in iPhone.

Challenges in handling search compared to domain specific applications:

- Complex grammar support is required

- Need to support huge vocabulary.

Metrics

-

WER:

\[WER = \frac{\text{No of substitutions} + \text{insertions} + \text{deletions}}{\text{Total number of words}}\] -

Semantic Quality (WebScore): WER is not an accurate depiction of usability of an ASR system. For eg, even if we error on some filler words like “a”, “an”, “the” etc, we can still reliably do accurate entity extraction. Hence, we should optimize on this metric rather than on WER.

Logic is simple. Take the output from ASR. Run it through the search engine and get the results. Take the correct transcription. Run it through the search engine and get the results. The amount of overlap between these two results shows how good/usable the ASR is.

Google’s WebScore is calculated as follows:

\[WebScore = \frac{\text{Number of correct web results}}{\text{Total number of spoken queries}}\] -

Perplexity: This is a measure of the how confident the system is about a result. Lower the perplexity, better the system is.

-

Out of Vocabulary (OOV) Rate: The out-of-vocabulary rate tracks the percentage of words spoken by the user that are not modeled by the language model. It is important to keep this number as low as possible.

-

Latency: Reaction time of the system. Total time taken from the user speaking to producing relevant results to him. Lower the latency, better the UX.

Acoustic Modeling

The details of these systems are extensive, but improving models typically includes getting training data that’s strongly matched to the particular task and growing the numbers of parameters in the models to better characterize the observed distributions. Larger amounts of training data allow more parameters to be reliably estimated.

Two levels of bootstrapping required:

- Once a starting corpus is collected, there are bootstrap training techniques to grow acoustic models starting with very simple models (i.e., single-Gaussian context-independent systems.

- In order to collect ‘real data’ matched to users actually interacting with the system, we need an initial system with acoustic and language models.

For Google Search by Voice, GOOG-411 acoustic models were used together with a language model estimated from web query data.

Large amounts of data starts to come in once the system goes live and we need to leverage this somehow

- Supervised Labeling where we pay human transcribers to write what is heard in the utterances.

- Unsupervised Labeling where we rely on confidence metrics from the recognizer and other parts of the system together with the actions of the user to select utterances which we think the recognition result was likely to be correct.

Model architecture:

39-dimensional PLP-cepstral coefficients together with online cepstral normalization, LDA (stacking 9 frames) and STC. The acoustic models are triphone systems grown from deci-sion trees, and use GMMs with variable numbers of Gaussians per acoustic state, optimizing ML, MMI, and ‘boosted‘-MMI objective functions in training.

Observed effects:

- The first is the expected result that adding more data helps, especially if we can keep increasing the model size.

- It is also seen that most of the wins come from optimizations close to the final training stages. Particularly, once they moved to ‘elastic models’ that use different numbers of Gaussians for different acoustic states (based on the number of frames of data aligned with the state), they saw very little change with wide ranging differences indecision tree structure.

- Similarly, with reasonably well-defined final models, optimizations of LDA and CI modeling stages have not led to obvious wins with the final models.

- Finally, their systems currently see a mix of 16 kHz and 8 kHz data. While they’ve seen improvements from modeling 16 kHz data directly (compared to modeling only the lower frequencies of the same 16kHz data), so far they do better on both 16 kHz and 8 kHz tests by mixing all of their data and only using spectra from the first 4 kHz of the 16 kHz data. They expect this result to change as more traffic migrates to 16 kHz.

Next challenge: Scaling

Some observations:

- The optimal model size is linked to the objective function: the best MMI models may come from ML models that are smaller than the best ML models

- MMI objective functions may scale well with increasing unsupervised data

- Speaker clustering techniques may show promise for exploiting increasing amounts of data

- Combinations of multi-core decoding, optimizations of Gaussian selection in acoustic scoring, and multi-pass recognition provide suitable paths for increasing the scale of acoustic models in realtime systems.

Text Normalisation

Google uses written queries to google.com in order to bootstrap their language model (LM) for Google search by Voice. The large pool of available queries allowed them to create rich models. However, they had to transform written form into spoken form prior to training. Analyzing the top million vocabulary items before text normalization they saw approximately 20% URLs and 20+% numeric items in the query stream.

Google uses transducers (FSTs) for text normalisation. See the Finite State Transducer section in blog post for an introduction to what transducers are.

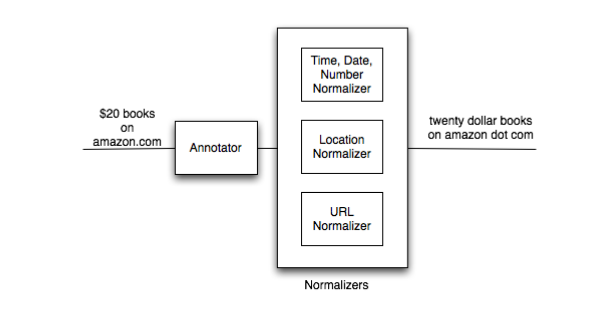

In the annotator phase, they classify parts (sub strings) of queries into a set of known categories (e.g time, date, URL, location). Once the query is annotated, each category has a corresponding text normalization transducer \(N_{cat}(spoken)\) that is used to normalize the sub-string. Depending on the category they either use rule based approaches or a statistical approach to construct the text normalization transducer. They used rule based transducer for normalizing numbers and dates while a statistical transducer was used to normalize URLs.

Large scale Language Modeling (LM)

Ideally one would build a language model on spoken queries. As mentioned above, to bootstrap they started from written queries (typed) to google.com. After text normalization they selected the top 1 million words. This resulted in an out-of-vocabulary (OOV) rate of 0.57%. Language Model requires aggressive pruning (to about 0.1% of its unpruned size). The perplexity hit taken by pruning the LM is significant - 50% relative. Similarly, the 3-gram hit ratio is halved.

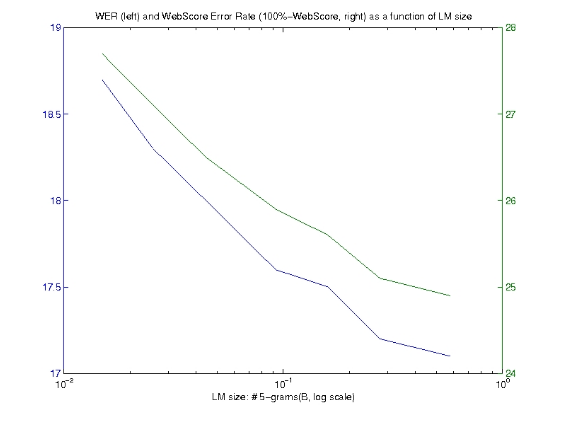

The question they wanted to ask was, how does the size of the language model affect the performance of the system. Are these huge numbers of n-grams that we derive from the query data important?

Answer was, as the size of the language model increased, a substantial reduction in both the Word Error Rate (WER) and associated WebScore was observed.

Locale Matters (A LOT):

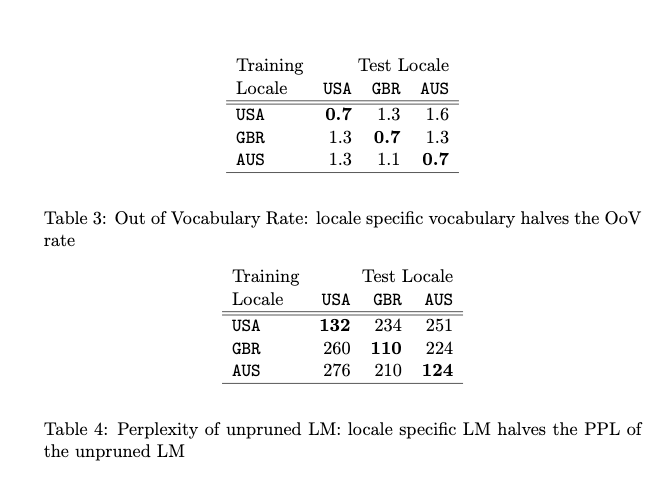

They built locale specific English language models using training data from prior to September 2008 across 3 English locales: USA, Britain, and Australia. The test data consisted of 10k queries for each locale sampled randomly from Sept-Dec 2008. The dependence on locale was surprisingly strong: using an LM on out-of-locale test data doubled the OOV rate and perplexity.

They also built a combined model by pooling all data. Combining the data negatively impacts all locales. The farther the locale from USA (as seen on the first line, GBR is closer to USA than AUS), the more negative the impact of clumping all the data together, relative to using only the data from that given locale.

In summary, locale-matched training data resulted in higher quality language models for the three English locales tested.

User Interface

“Multi Modal”: Meaning different forms of interaction. For eg, telephone is a single modal UI since the input and output is voice. Google Search by Voice is multi modal since input is voice and output is visual/text and similarly, Maps is multi modal since input is voice and output is graphics.

Advantages of multi modal outputs:

-

Spoken input vs output

There are two different scenarios in using Search by Voice. If we are searching for a specific item, single modal response is a good UX. If we are searching using a broader term for search or the user wants to explore/browse further, single modal results in a bad UX. The following illustrates this:

Good UX:

GOOG411: Calls recorded... Google! Say the business and the city and state. Caller : Patxi’s Chicago Pizza in Palo Alto. GOOG411: Patxi’s Chicago Pizza, on Emerson Street. I’ll connect you...Bad UX:

GOOG411: Calls recorded... Google! Say the business and the city and state. Caller : Pizza in Palo Alto. GOOG411: Pizza in Palo Alto... Top eight results: Number 1: Patxi’s Chicago Pizza, on Emerson StreetTo select number one, press 1 or say ”number one”. Number 2: Pizza My Heart, on University Avenue. Number 3: Pizza Chicago, on El Camino Real.[...] Number 8: Spot a Pizza Place: Alma-Hamilton, on Hamilton Avenue -

User control and flexibility:

Unlike with voice-only applications, which prompt users for what to say and how to say it, mobile voice search is completely user-initiated. That is, the user decides what to say, when to say it and how to say it. There’s no penalty for starting over or modifying a search. There’s no chance of an accidental “hang-up” due to subsequent recognition errors or timeouts. In other words, it’s a far cry from the predetermined dialog flows of voice-only applications.

The case study explored further on UI/UX observations regarding visual interfaces, including how and where the button should be placed, how to show the ASR alternatives, intent based navigation to apps (Drive to vs Navigate to) etc